Failure of EPA Fukushima U.S. Radiation Monitoring

With a plume of radioactivity headed to the U.S. from the three melting reactors in Japan, Environmental Protection Agency personnel scurried to send out sensitive deployable radiation monitors to fill in large gaps along the American West Coast where no stationary air monitors existed. Then, inexplicably, officials at EPA headquarters in Washington ordered the radiation monitors not be deployed. Most sat in offices and warehouses throughout the accident, taking no measurements.

Bridge the Gap revealed to the news media that half of EPA’s stationary air monitors across the country were broken at the time of the accident; many had been not working for months. Even had they been working, they couldn’t measure most radioactive iodine, one of the primary radionuclides of concern.

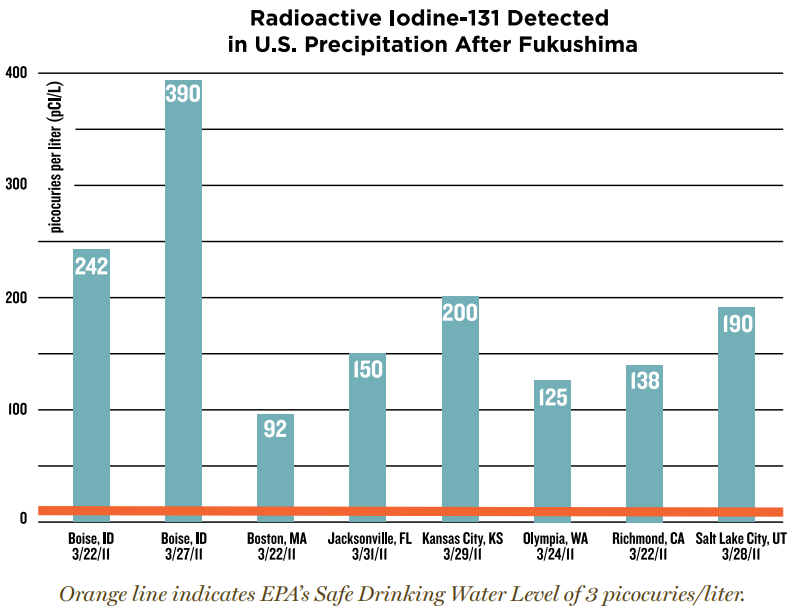

EPA kept quiet about any radioactivity showing up in precipitation until the States of Massachusetts and Pennsylvania announced their own measurements showing significantly elevated levels of radioactive iodine. EPA then started reluctantly releasing other measurements of rain and snow, yet tried hard to bury the findings. Precipitation across the country was found to contain radioactive iodine (I-131) at levels greatly in excess of the EPA’s Safe Drinking Water Levels (see graph at right). EPA, instead of making this clear, tried to walk away from its own standards.

We also revealed that milk samples are generally held for six months to a year before being monitored for strontium-90, so that if contamination is found, it will be far too late to take steps to protect anyone, since the milk will have long since been consumed. And EPA, when elevated iodine-131 was found in milk, compared the levels not to its own Safe Drinking Water standards but to other levels thousands of times less protective.

This was troubling because for years, Bridge the Gap has been pushing against EPA efforts to dramatically weaken radiation guidelines that are to be used in dealing with a release of radioactivity. In the last hours of the George W. Bush Administration, EPA officials tried to publish in the Federal Register revised Protective Action Guides (PAGs) that would have increased allowable radioactivity levels in drinking water by factors of a thousand or more. The proposed PAGs would have also allowed long-term contamination so high that EPA’s own estimates were that as many as one in four people exposed would get a cancer from the contamination.

Working with a coalition including NRDC, Sierra Club, Physicians for Social Responsibility, Nuclear Information & Resource Service, and others, we got the new Administration to withdraw the proposed PAGs and undertake a review. Nearly three years later, no new PAGs have been issued, the problems remain unresolved, and press reports indicate that the Obama Administration is considering almost the same weakening of protections that its predecessor did, albeit using different words.

This November, CBG’s Dan Hirsch, with a coalition of other groups, presented findings to EPA senior management of a 6-month study of the extraordinary failures of the EPA Fukushima radiation monitoring program in the U.S. and concerns about continued efforts at EPA to weaken radiation standards. The briefing included the EPA Deputy Administrator and the Assistant Administrators for Air and Radiation, for Water, and for Emergency Response.

If the EPA U.S. radiation monitoring system is incapable of seeing elevated radiation when it occurs, or downplays it even when it can see it, EPA will be incapable of taking actions to protect the public. And if the Protective Action Guides are based not on radiation levels that are in fact protective, but that are weakened thousands of time from generally accepted standards, people won’t be protected at all.

In Japan, a furor arose when authorities attempted to relax radiation standards, including those for children, from 0.1 rem per year to 2 rem, in part because of high radiation levels in children’s schoolyards. These levels would cause a cancer in one out of every two hundred children, according to official risk estimates. The Japanese authorities were forced to back off, at least in part. What was not revealed, however, is that EPA’s Protective Action Guides in this country permit precisely the same outrageously high exposure levels.

Bridge the Gap will keep fighting for radiation monitoring systems that work and protective action guides that are protective.