SRE Meltdown Anniversary

High resolution images, videos are available for viewing, as well as

.pdf documents

In November of 1957, Edward R. Murrow’s “See It Now” television show was present to film when the Sodium Reactor Experiment (SRE) was tied into an Edison substation to light the town of Moorpark, supposedly the first time a nuclear reactor produced commercial electricity, a PR effort by the Atomic Energy Commission.

About a year and a half later, the SRE reactor suffered a partial meltdown, one of the worst accidents in nuclear history to that date. It appears the AEC never got around to notifying Murrow that there might be a newsworthy followup to his earlier piece. Indeed, news of the accident was suppressed for twenty years until students at UCLA found AEC records of the accident and released them to the news media. At the time, all AEC did was release a press release, embargoed for Saturday papers, about five weeks after the accident, that said merely “a parted fuel element had been observed,” and that there were no radioactive releases nor any evidence of unsafe operating conditions. In fact, the fuel had experienced melting, not merely “parting,” one third of the fuel was damaged, the facility had been venting radioactive gases into the environment for weeks, and it was clear evidence of unsafe operating conditions.

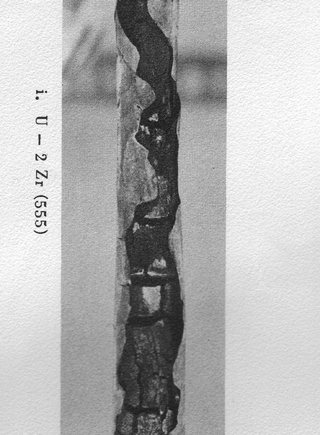

This photo shows some of the extensive damage that nuclear materials sustained as a result of the SRE partial meltdown

What Happened in July 1959

Run 14 began in July 1959. In previous runs, there had been evidence of tetralin leaking into the sodium coolant. Rather than resolving the problem, they started a new run. This led to the meltdown.

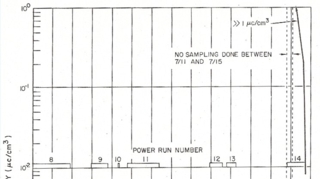

Radioactivity levels went off scale, as shown in this chart excerpted from an Atomics International chart

The Sodium Reactor Experiment, as the name implies, used sodium—a metal that becomes a liquid at high temperatures—as it coolant, rather than water as used in most commercial reactors today. (Sodium coolant would be used in the breeder reactors that nuclear advocates are pushing be used now to “recycle” plutonium; the SRE accident raises serious questions about this current push.)

Sodium burns in the presence of air and explodes in the presence of water, so it must be kept isolated from both. Therefore, the pumps that pump the sodium into the core had to be cooled with something other than water; they used tetralin, an organic coolant.

In reports describing the SRE incident, scientist/engineers use highly technical terms such as “melted blob.”

However, tetralin leaked through the pump seals and into the sodium coolant. It globbed up, becoming a tar-like substance that clogged the fuel’s coolant channels. The sodium coolant thus couldn’t cool the nuclear fuel, and the fuel overheated; the steel cladding and the uranium fuel “meat” formed a low-melting alloy (a “eutectic”) and melted.

On July 13, the reactor experienced a “power excursion,” in which power runs out of control. The operators tried desperately to shut the reactor down, but even as they were jamming control rods in, the power kept rising. They eventually managed to shut it down, but inexplicably, after a couple of hours, without being able to figure out what had gone wrong, they started it up again.

They kept running it for nearly two weeks, in the face of high radiation readings, more scrams (emergency shutdowns), and all sorts of other indications of fuel damage. When they finally shut it down on July 26, they discovered that one third of the fuel elements had experienced melting.

The reactor had no containment structure, the thick concrete domes around modern reactors. There thus was no way to contain radioactivity so as to prevent its release into the environment. Indeed, radioactive gases from inside the reactor (the “core cover gas”) were intentionally pumped out of the reactor into tanks and then intentionally vented into the atmosphere.

Radioactivity levels during the accident went off-scale –i.e., were “hotter” than the instruments could measure. We thus do not know, to this day, how much radioactivity was released.

Current Situation

The SRE was located at what is now called the Santa Susana Field Laboratory (SSFL), now operated by Boeing. SSFL housed, in addition to the SRE, nine more reactors (at least three of which also suffered accidents), half a dozen “critical” nuclear facilities (a variant on a reactor), a “Hot Lab” in which highly irradiated nuclear fuel from around the AEC/DOE nuclear complex nationally was shipped in to be cut apart, and a plutonium fuel fabrication facility. Radioactive and chemically contaminated reactor components were also burned—illegally—for decades in open pits. Also, tens of thousands of rocket tests were conducted at the site.

All this activity resulted in accidents, releases, and spills that produced widespread radioactive and chemical contamination at the site. On the radioactive front alone, about a quarter of a billion dollars has been spent to date trying to clean up the contamination, and we are still far from the cleanup being over. Recently, DOE provided EPA $40 million in stimulus funds for an EPA radiological survey to locate and characterize the radioactive contamination.

Implications for the Present Debate on Reviving Nuclear Power

Nuclear advocates have been pushing aggressively for a revival of all things nuclear. This an only occur if there is a kind of “nuclear amnesia”—in which the public forgets what went wrong the last time we tried this. Forgetting the meltdown in Los Angeles is one piece of this hoped-for forgetfulness.

Industry is, at this moment, pushing for $50 billion in loan guarantees (one proposal would be for unlimited guarantees) for new nuclear plants in the energy and climate bills going through Congress. There has been essentially no coverage of this. The mess made the last time should be a wake-up call.

In the same legislation, there is a push to end the 30-year moratorium on reprocessing irradiated fuel to extract its plutonium and run it in sodium-cooled reactors (a moratorium put in place by Presidents Ford and Carter because of proliferation concerns.) Again, this can only occur if we forget the past.

Those who fail to remember the past are condemned to repeat it, and repeat it, and repeat it.